Will we choose songs and hymns I like? What’s for lunch later?

These are the questions that occupy many minds as we set out for church. In this second article of our series, expanding on our church’s “Book of the Term”, “How To Walk Into Church” (Tony Payne), here are two better questions as I come to church:

1. How should I respond to God?

The word “worship” comes from Old English “weorthescipe” – ascribing value or “worth” to something. So a good house could be a “place of worship” and a leading town like London a “city of worship”. The Prayer Book marriage service expects the groom to say to his bride, “With my body I thee worship”! No-one is saying that the house, city or bride is divine!

“Worship” (the Greek word proskynēo) in Matthew 2:2 (the wise men came to worship the newborn child) can just mean “fall on our knees”. Thus our English word “worship” has a wider meaning than the Greek one (we take it to include singing and praying, not just kneeling) but also a narrower one (we tend to think only of worship in ‘church’, not in common life as well).

So here’s a definition (with acknowledgement of DA Carson’s much longer equivalent):

Worship is the proper and delighted response to God’s majesty in creation and redemption in Christ, both in all of life and when we gather as ‘church’.

So worship is above all God-centred: a joyful response to who God is. See for example Revelation 4:11, “you alone are worthy to receive glory and honour and power, for you created all things”.

What makes worship delightful is the object at its centre. Worship is not creating something new but responding to the already-present majesty and mercy of God. And Christ is central as the One who shares the throne of God, and who redeemed us by his blood. This God-centredness is vital for churches to recover in a world where so many things (eg career, self, possessions) call us to worship them instead.

The New Testament transforms Old Testament worship. Where Israel had priests, the church has the priesthood of all believers. The covenant sacrifice of bulls and goats is fulfilled in the sacrifice of Christ. The tabernacle and the temple which symbolised God’s dwelling on earth are fulfilled in the body of Jesus (John 2:21), or of the Church (Ephesians 2:22), or of the believer (1 Corinthians 6:19). Hebrews 12 reminds us that we worship God not on a physical mountain but on Mount Zion, the heavenly Jerusalem, along with angels and saints, and through Jesus’ blood.

Romans 12:1-3 is a key Bible verse in understanding worship: “in view of God’s mercy, offer your souls and bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God, for this is your reasonable act of worship.” Here Paul uses a second word-group for “worship” (Hebrew abodah, Greek latreia) which means “work/service/activity”.

Worship is as much action for God – what we do the rest of the week with our souls and bodies – as adoration – how we adore Him on Sunday. So I can’t worship God on Sunday if I have not done so during the week. My weekday worship prepares me for that on Sunday (and vice versa).

A good way to prepare for Sunday is to pray for the preacher to be faithful and inspired in what they teach. Pray for the congregation and any newcomers to be attentive and to have lives changed by the gospel message. Pray for any particular people we know who are anxious, or doubting, or discouraged. Read the passage that is being taught about in the sermon if your church has told you what it is in advance.

So come to church ready for action! Here’s the second great question on the way to church:

2. How can we help to build each other up?

David Peterson argues (from eg 1 Corinthians 14, see v26) that the New Testament’s emphasis in gathered worship is upon encouraging each other. Sunday best clothing should be hard hats and boots, because we are to “build” each other up. He’s right that I can sing songs at home, or pray at work, but I cannot encourage and edify you except when we gather.

Anglican worship is historically strong at ‘building up’ the faith of the congregation. Thomas Cranmer, reforming Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry VIII and Edward VI, saw three things that gathered worship must be:

Biblical – our gathered ‘church’ should be drenched in Scripture, not just in the reading and sermon, but in the content of songs and prayers. Even the plan of the service comes from Scripture, including the elements of worship listed in the Biblical accounts: invitation to praise and prayer, songs of praise, confession, reading of Scripture and explanation of it, sharing of food and of gifts for the poor, sacraments of baptism and communion. In all these moments of ‘church’, the common feature is faith responding to the Word of God.

Balanced – churches today tend to either cut out the past with some of the best prayers and music, or to cut out the present with its new ideas which can enhance our worship. Thomas Cranmer followed the principle of emphasising what the Bible emphasises (God’s grace, Word and gospel signs; the people’s repentance, responsiveness and obedience) and being silent where the Bible is silent (eg the kind of music, or whether to stand, sit or kneel). He kept the best prayers from the past, but rewrote the Roman Catholic service. He included the congregation much more in singing and saying the Bible and prayers, where before the priest said everything. He took out ceremonies which undermine faith in Christ, but encouraged those which promote it.

Intelligible – Cranmer put the words of the services into English, from a Latin which even many priests leading the medieval services did not understand. He adapted or wrote many new prayers or Collects, especially his excellent “Collect for Bible Sunday” (Last Sunday after Trinity) . He simplified gathered worship for the congregation by putting it all in one book, where before there were half a dozen to juggle. Were he here today he would doubtless have put prayers online and in apps!

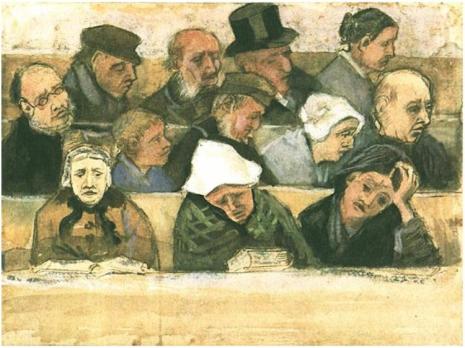

So what does it mean to come to church ready to build each other up, as Cranmer saw so clearly? I need to come ready to sing enthusiastically and to join in loudly with the prayers which the congregation says together: the point is that we are all joining in! I need to come ready to listen to the words of the whole service thoughtfully, as the words of songs, hymns and prayers may carry gospel truths as important to me as those of the sermon. And I need to encourage the people around me by joining in at all points, including listening to and taking notes on the sermon. As Tony Payne puts it, don’t be a “dipping duck” nodding off in the pew, or drift off looking for invisible fairies in the ceiling! As I respond to God with enthusiasm, I build up those around me too.

Are you ready to come to church?

Further reading

DA Carson (Editor) Worship by the Book (Zondervan, 2002)

John M Frame, Worship in Spirit and Truth (P&R, 1996)

David Peterson, Engaging with God (IVP/Apollos, 1992)

Thomas Cranmer’s Collects can be found in the Book of Common Prayer, or the modern adapted versions of them online. They are delightfully presented with commentary in

C Frederick Barbee & Paul F M Zahl, The Collects of Thomas Cranmer (William B Eerdmans, 1999)